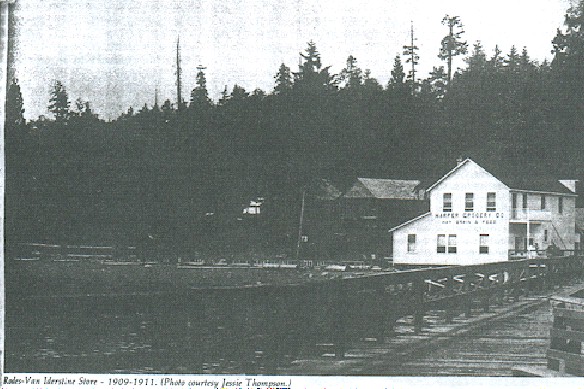

“Downtown” Harper about 1916, with the steamship pier in the foreground. The store on the beach was owned by Thomas Grant.

By Russell Neyman.

In her lengthy accounts of pioneer life in the Harper region, Miriam Grant went into detail how, exactly, the town got its name. The events that led up to that decision reveal how life was in the 1880’s through to the turn of the century. In 1900, it seems that a young man, Frank Harmon, made the long and difficult journey through the heavy brush and deep creeks from his family homestead on the Southern shore of Yukon Harbor to the Grant & Sons Mercantile in Colby once a week to pick the mail.

That trip – today it would require a five-minute drive down Southworth Drive, crossing the Curley Creek bridge, and bearing right on Yukon Harbor Drive – was an all day ordeal, following crude footpaths and negotiating the many streams as best he could. After what was a half day hike, he arrived at the store where the nearest post office was located, picked up the mail for his family and neighboring families. Even when the weather was good, it was a four to six-hour journey.

Mail in hand, his journey was only half done. Rather than re-trace the same route laden with all sorts of packages and, probably, supplies purchased from the Grant & Sons store, he usually chose to take a commercial ship back. The so-called “Mosquito Fleet” steamers typically circulated in a counter-clockwise direction, starting in Poulsbo, passing through Port Orchard (Sidney), Annapolis, Waterman, Manchester, and Colby, so homeward leg would be a quick one, provided he could connect with a ship. The last stop before returning to Seattle was the point of land opposite Blake Island, commonly known as “Harmon’s Landing,” after the family name.

The process in those days, when there was no pier or formal steamship landing, was to have one of the Grant boys row George and his packages out to a float anchored a hundred feet out in the Sound, where he would wait for a boat to arrive. He often returned home from his weekly trek cold, wet and tired,

Needless to say, after several years the Harmons grew weary of the arrangement, and decided to secure their own post office. The proper paperwork was obtained, and Frank sat down at the Harmon kitchen table to complete the application. His mother, a Yaqui Indian who had learned the White man’s ways, was cooking. Miriam Grant (who was, by the way, not related to the owners of the Grant & Sons business) was there, too, and wrote about the scene.

We need to interject a few words here about how towns and places got their name: The need for names for places was required in order to communicate a destination with a traveler or steamship captain. For clarity and convenience, locations would often be informally named for a geographical feature or for the family who lived in that place, but it was not until a post office was installed that a permanent name was required. (See the feature, “Place Names,” elsewhere on this website.)

Paraphrasing her Miriam Grant’s account, here is what transpired:

“Mother, the authorities want to know what name we will designate for our new post office,” Frank said. “Should we call it Harmon’s Landing? That’s what most people call this place.”

“Oh, no, it would be too immodest to name it after ourselves,” Jenny Harmon replied, sternly.

“Hmmm,” thought her son, “Mr. Harper will be building a new brick factory up the shoreline, so why not designate the post office as ‘Harper’?”

Jenny, in her broken English, muttered something like, “That would be acceptable.” And the decision that would last a hundred years and more was made as casually as that; the place previously known as “Harmon’s Landing” ceased to exist and a new entity replaced it during the course of a two-minute conversation. The Harper Post Office opened on December 11, 1900.

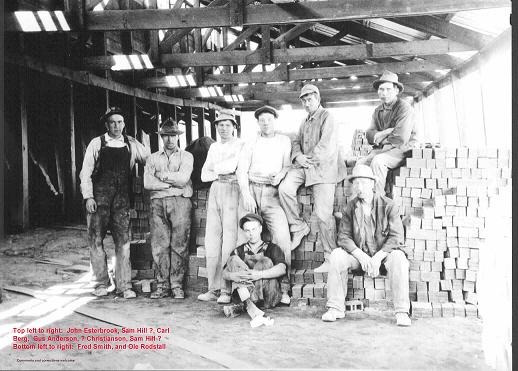

The community’s namesake was Frederick Harper, a former state representative, customs officer, and entrepreneur. A high grade clay suitable for manufacturing bricks had been found on the hills near the creek to the south about 1896 on the Issac Grant property, and Harper and a few investors built the factory with several outbuildings. There were kilns, a molding shed, a bunkhouse/hotel, an office, and a small railroad track to transport the clay from the quarry down to the factory. It opened about 1920 and closed in the early 30’s.

This extremely rare view of Harper shows the drawbridge that crossed the bay, allowing brick barges to be hauled to and from Frederick Harper’s Brick Factory, which was where a small Little League field is now. The placard welcomes visitors to Olympic National Park, one of the nation’s first such reserves.

Frank’s father, George Harmon Sr., was born in November of 1842 in Germany, immigrating to the United States in 1858. He arrived aboard the first battleship ever to enter Puget Sount, USS DECATUR*, probably as an ordinary seaman. In the early 1870’s, Harmon (whose given name might have been spelled Harmann, as noted on the 1910 Census) filed a homestead at the point of land between South Colby and Southworth and began to build a future. His occupation was primarily as a fisherman, but he established a small lumber mill, planted trees, and built a modest cabin on the hill above the beach facing east, near Harper Hill Road. To facilitate and encourage steamships to stop at his place, he piled up rocks at the shoreline to form a small breakwater so that smaller boats could nose up on the beach without capsizing.

How, exactly, the elder George Harmon met his wife is a telling story about how men lived at the time. In 1874, with his homestead established, he decided a wife would make his life more full, but who would he marry? The ratio of males to females in Washington Territory at that time was roughly 20-to-1. Reading in the local newspapers that “a boatload of women eager to be married” was scheduled to arrive in Seattle, Harmon decided to take the plunge.

He loaded his small fishing boat and headed to Seattle, a trip of several hours even in fair weather. Unfortunately, he arrived a couple of hours late, and by that time all the eligible ladies had been taken by the hundreds of suitors who were also “in need” of a spouse. Sitting on the pier was a Native American woman, Jenny Kelly, who was from a tribe located in the Arizona Territory. “How about you?” he asked her. “Do you want to be married?”

She agreed, and they were married that year. The United States Census records are confusing, but they may have had as many as five children together – George Jr, Frank, Hattie, and Emma Louisa, and William Anthony. Hattie probably died as a child, because there is no mention of her after 1910. Childhood deaths were commonplace at that time in the Yukon Harbor area.

George E Harmon, Sr., died in December of 1917, aged 77.

After her husband passed away, Jennie Harmon continued to live in the family house on Harper Hill road, becoming somewhat of local character. She was interviewed by a newspaper reporter in her final few years and made note of how the region had changed in her lifetime. “In the beginning, there were only about 50 Whites,” she said. “Now, there are too many, and there is no peace.”

She was a small woman, wore her hair in a long braid, and spoke a sort of pigeon English. In contrast to her Yaqui ways, she was known to wear the Victorian fashions of the era, with full dresses that featured petticoats and hoops.

Details of her early life are sketchy, but she noted in that interview that she had been married prior to meeting George. Her first husband drowned in a canoe accident. Over the span of both marriages she gave birth to ten children and out lived many of them.

Jennie claimed to be related to Chief Seattle, telling one interviewer that “he was my mother’s uncle.” She related details of visiting the Suquamish chief’s long house, noting that “it was extremely large.”

She was probably born in Washington Territory, even though her tribal roots were in Arizona. One Census indicates that she was born in 1817; that would have made her 118 at the time of her death in 1937, which is extremely unlikely. In her later years she indicated she really did not know the year of her birth.

The original Harmon homestead was 160 acres. By the time of Jennie’s passing that had been reduced to eight.

Born in 1880, the oldest son, George Junior, did not easily integrate into society, probably because he was a so-called “half breed.” He was married but by 1920 was widowed, with no known children. Like his father, he mostly fished, but also made small pieces of furniture and did odd jobs. For a time in the 30’s he resided in Waterman, but eventually moved back to Colby, living in a shack on the beach near the lumber mill. He was known as simply “Indian George.”

The locals who grew up here in the 1930’s and 40’s remember him as a loner who was frequently drunk, living a hardscrabble life. This, obviously, did not sit well with the pious Methodists who resided in the town. His ramshackle house was extremely small – perhaps only 80 or 100 square feet – and heated by a small potbellied stove. He often caught and smoked fish, trading it for supplies or alcohol.

JoAnn Lorden has only fleeting memories of him, but offered this:

“Indian George was scary. It was pretty clear that he was drunk most of the time, so we kids were told to stay away from him.

“The times that I was near enough to George to hear him talk to my father I was eight or ten years old. He looked tall and skinny and very dark. Since he was only half Indian maybe his dark skin was due to sleeping in his boat in the sun a lot. He sounded uneducated when he talked. It could be that he spoke Pigeon English.

“If George did go to school it would have had to be Colby I would think. A thought that I have had about him is that he appeared to be very poor and I wonder where he got liquor to drink –which we all knew he did. I wonder if he made moonshine and what his recipe might have been. I assume that George lived on fish, clams and berries.”

Lorden continues: “I have also wondered how he got the little shanty that he lived in on the beach in Colby. There must have been someone who knew something about him and maybe even looked after him in his later years.

“There used to be another Indian who lived in a shack on the Annapolis ferry dock. His name was Codfish and he carved funny looking figures out of wood. I was as afraid of Codfish as I was of George and gave both of them a wide berth. Every Saturday morning I had to take the little ferry from Annapolis to Bremerton to my dance class. It took a lot of courage to walk past Codfish’s shack coming and going.

“My mother encouraged me to go places by myself that I would never have done with my own kids later in life ”

Lorden further relates that Indian George was often seen sleeping in his small rowboat, presumably in a drunken stupor, a story confirmed by the McFate family and other locals who lived in Colby in the 30’s and 40’s. “One time the boat drifted away with him in it, being pulled around the bend and into the Colvos Passage current.”

Earl Whitner, who grew up in Colby, relates a story about Indian George that was passed on to him by his mother. One afternoon Mrs. Whitner was visiting with other local women, and commented, “Poor Indian George came to me the other day, complaining about another rotten tooth that needed to be pulled, so I gave him a dollar. He’s come to me several times recently asking for help paying the dentist.”

“Oh, really…?” said one of the other women. “Strange…. He begged me for money to have a tooth pulled, too, a few weeks ago.” The third woman related a similar story. After adding up all the dental problems it was a wonder Old George had any teeth at all.

George was, it was surmised, “cashing in his teeth” to purchase beer. Since no alcohol was ever sold in Colby, he was forced to walk to Manchester to make his purchase.

Earl recalls one event from his teen years when he saw Indian George comatose in the snow along the road near what is now Colchester, apparently frozen to death. It was believed that he had passed out after a drinking binge, but he somehow survived that ordeal. He passed away in 1951, just three weeks short of his 72nd birthday, in Indianola, Washington, a town populated by many Native Americans.

William H Harmon died in 1920 in Seattle, and the other brother, Frank, 14 years younger, lived until 1955. No records of the other second-generation Harmons are yet available.

The smaller steamers that were the backbone of everyday transportation were built in small boat shops, like this one believed to have been located in Harper. This photo shows the NINA E being launched. Below, the THERESA is also launched from the boatbuilding same shop, which may have been run by the Foss family. Photos provided by Shirlee Toman.

In a region known for lumber, Harper gained a measure of notoriety for another building material – bricks. A pier was built in the early 1900’s, and it proved sturdy enough to serve as one of the county’s very first automobile ferry terminals, with the first cars unloading about 1922. One of the ferry captains, a Mr Shaw, lived on Cole Loop (formerly First Street) for decades and was a familiar face to both Lorden and Whitner. That pier — or, at least, a third generation structure at the same location, as it had been rebuilt several times — was finally torn down in early 2013.

The community never really blossomed into a full-blown town. The pieces were there – a post office, church, school, and one or two stores – but they were scattered here and there and there was no “town center.” Other than Frederick Harper’s brick factory located at the creek estuary to the south of the Harmon homestead and the accompanying bunkhouse, there never really was a group of buildings. The Cornell family built a store on the beach front, but it was marginally profitable and did not last. The brick factory closed about 1930, leaving the community without a primary business. The pieces of the town were scattered here and there, effectively becoming a suburb of Colby.

The Harper dock (above) was one of the very first auto ferry piers built on Puget Sound. Service began about 1925, and a rebuilt several times. It was removed in 2013.

__________________________________________________

Notes:

* We find no record of any battleship by the name of DECATUR.

>> Much of the background information included here was provided by contributor and genealogist JoAnn Lorden. Her sources were:

- “Washington Death Certificates, 1907-1960,” FamilySearch.org

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints website

- Various United States Census records.

>> A second key source is the memoir collection from Miriam Grant, provided to YHHS by Ann Northcutt Levenseller.

>> Further information was taken from Kitsap County, A History, published by the Kitsap County Historical Society.

>> This is one of those stories that is ongoing and will evolve. We expect to hear from family members who can shed additional light and, hopefully, photographs about the Harmon family.

Thanks for the article! According to my father, Ed McFate, Indian George was often in his boat, afloat in Yukon Harbor. Jessie McFate, Ed’s mother and resident of South Colby from 1908 – 1972, purchased fish from Indian George.

We heard those stories, too. On at least one occassion, that rowboat drifted away with Indian George asleep in it, carring him down the passage toward Olalla.

Do you have any pictures of South Colby Texaco or know of anybody who might? Debbie, George & Dorothy Fraki say hi!

Hi Neighbors!

Great to hear from you! I don’t have any pictures of the Texaco, but have been looking for them. I was in touch with one of the Wright daughters this summer, but we haven’t found any photos yet. Where are the Frakis now? I live in Houston, Texas. Kris is in South Colby and I come up for a visit every summer. Please send me an email at jeffjoylee@earthlink.net.

Joy (McFate) Lee

Except for the date being off by two years, “. . . immigrating to the United States in 1858. He arrived aboard the first battleship ever to enter Puget Sound, USS DECATUR” may be a factual statement even though there was no battleship–as in a class of warship–named USS DECATUR.

The class of warships that we familiarly know as “battleships” did not come around until the late 19th century, but warships in the sail driven ship ages prior to that were often called “battleships,” which is was short for the phrase “line of battle ship.”

The first U.S. naval warship to enter the waters of the Puget Sound was the sloop of war USS DECATUR in 1855. In addition to Navy sailors and Marines, her crew consisted of European immigrants and native Hawaiians, which is why it is very possible that Mr Harmon was among her crew. Is it possible that saying he immigrated in 1858 is a mistake and that he actually immigrated two years prior to that? Or, is it possible that he did arrive when the USS DECATUR was in Seattle in 1855 and 1856, but did not receive citizenship until 1858?

Also, the USS DECATUR holds her own piece of history in the Yukon Harbor area. In December of 1855, she ran aground on what was then an uncharted reef off of Restoration Point at the southeastern tip of Bainbridge Island. Since then that reef became charted, and to this day is named Decatur Reef.

In January of 1856, the USS DECATUR took part in the Battle of Seattle, fighting against native Americans who were attacking Seattle settlers.